Eric Elliott’s exceptional Composing Software series is initially what got me excited about functional programming. It’s a must-read.

At one point in the series, he mentioned currying. Both computer science and mathematics agree on the definition:

Currying turns multi-argument functions into unary (single argument) functions.

Curried functions take many arguments one at a time. So if you have

greet = (greeting, first, last) => `${greeting}, ${first} ${last}`;

greet('Hello', 'Bruce', 'Wayne'); // Hello, Bruce WayneProperly currying greet gives you

curriedGreet = curry(greet);

curriedGreet('Hello')('Bruce')('Wayne'); // Hello, Bruce WayneThis 3-argument function has been turned into three unary functions. As you supply one parameter, a new function pops out expecting the next one.

Properly?

I say “properly currying” because some curry functions are more flexible in their usage. Currying’s great in theory, but invoking a function for each argument gets tiring in JavaScript.

Ramda’s curry function lets you invoke curriedGreet like this:

// greet requires 3 params: (greeting, first, last)

// these all return a function looking for (first, last)

curriedGreet('Hello');

curriedGreet('Hello')();

curriedGreet()('Hello')()();

// these all return a function looking for (last)

curriedGreet('Hello')('Bruce');

curriedGreet('Hello', 'Bruce');

curriedGreet('Hello')()('Bruce')();

// these return a greeting, since all 3 params were honored

curriedGreet('Hello')('Bruce')('Wayne');

curriedGreet('Hello', 'Bruce', 'Wayne');

curriedGreet('Hello', 'Bruce')()()('Wayne');Notice you can choose to give multiple arguments in a single shot. This implementation’s more useful while writing code.

And as demonstrated above, you can invoke this function forever without parameters and it’ll always return a function that expects the remaining parameters.

How’s This Possible?

Mr. Elliot shared a curry implementation much like Ramda’s. Here’s the code, or as he aptly called it, a magic spell:

const curry = (f, arr = []) => (...args) =>

((a) => (a.length === f.length ? f(...a) : curry(f, a)))([...arr, ...args]);Umm… 😐

Yeah, I know… It’s incredibly concise, so let’s refactor and appreciate it together.

This Version Works the Same

I’ve also sprinkled debugger statements to examine it in Chrome Developer Tools.

curry = (originalFunction, initialParams = []) => {

debugger;

return (...nextParams) => {

debugger;

const curriedFunction = (params) => {

debugger;

if (params.length === originalFunction.length) {

return originalFunction(...params);

}

return curry(originalFunction, params);

};

return curriedFunction([...initialParams, ...nextParams]);

};

};Open your Developer Tools and follow along!

Let’s Do This!

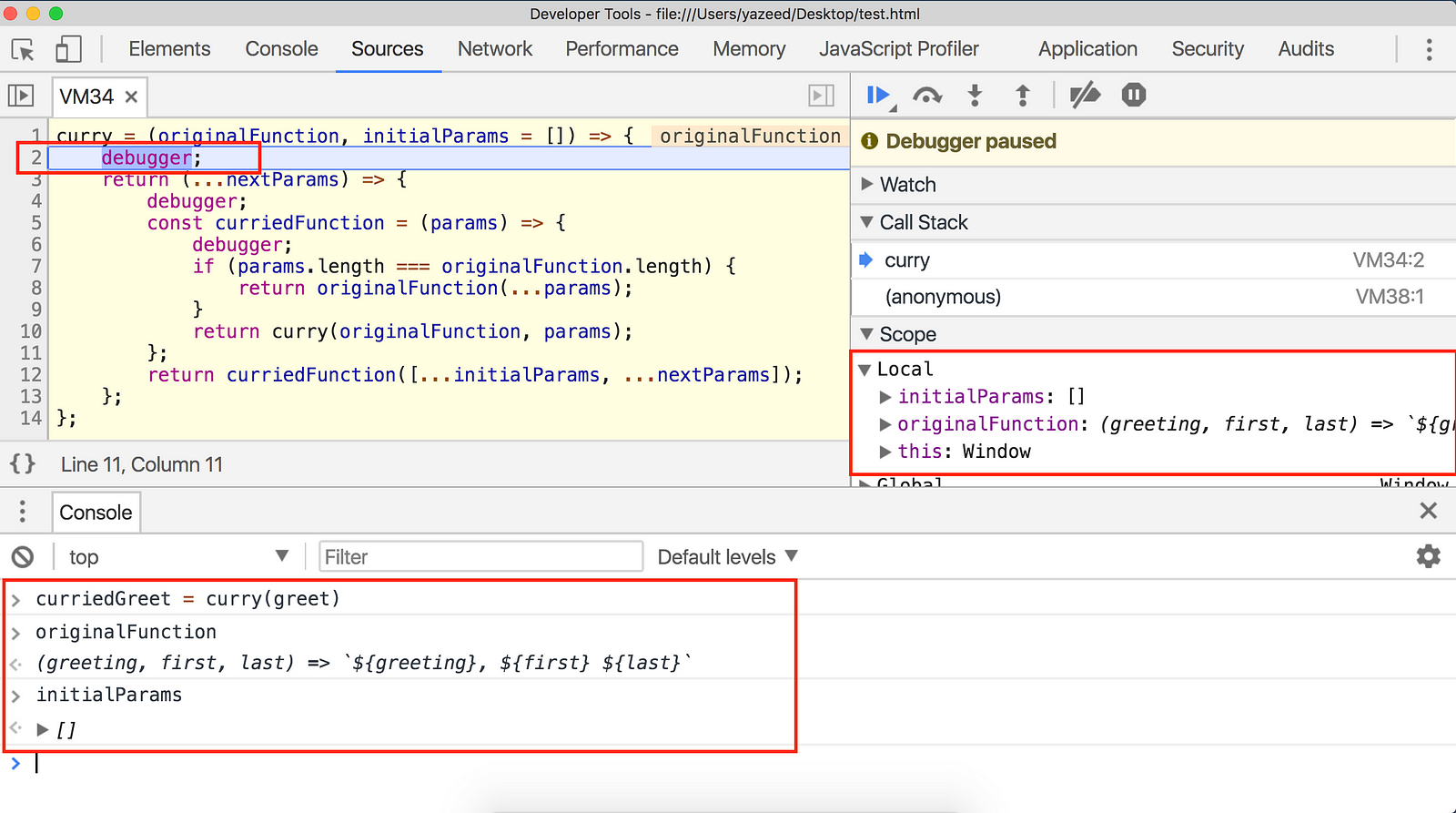

Paste greet and curry into your console. Then enter curriedGreet = curry(greet) and begin the madness.

Pause on line 2

Inspecting our two params we see originalFunction is greet and initialParams defaulted to an empty array because we didn’t supply it. Move to the next breakpoint and, oh wait… that’s it.

Yep! curry(greet) just returns a new function that expects 3 more parameters. Type curriedGreet in the console to see what I’m talking about.

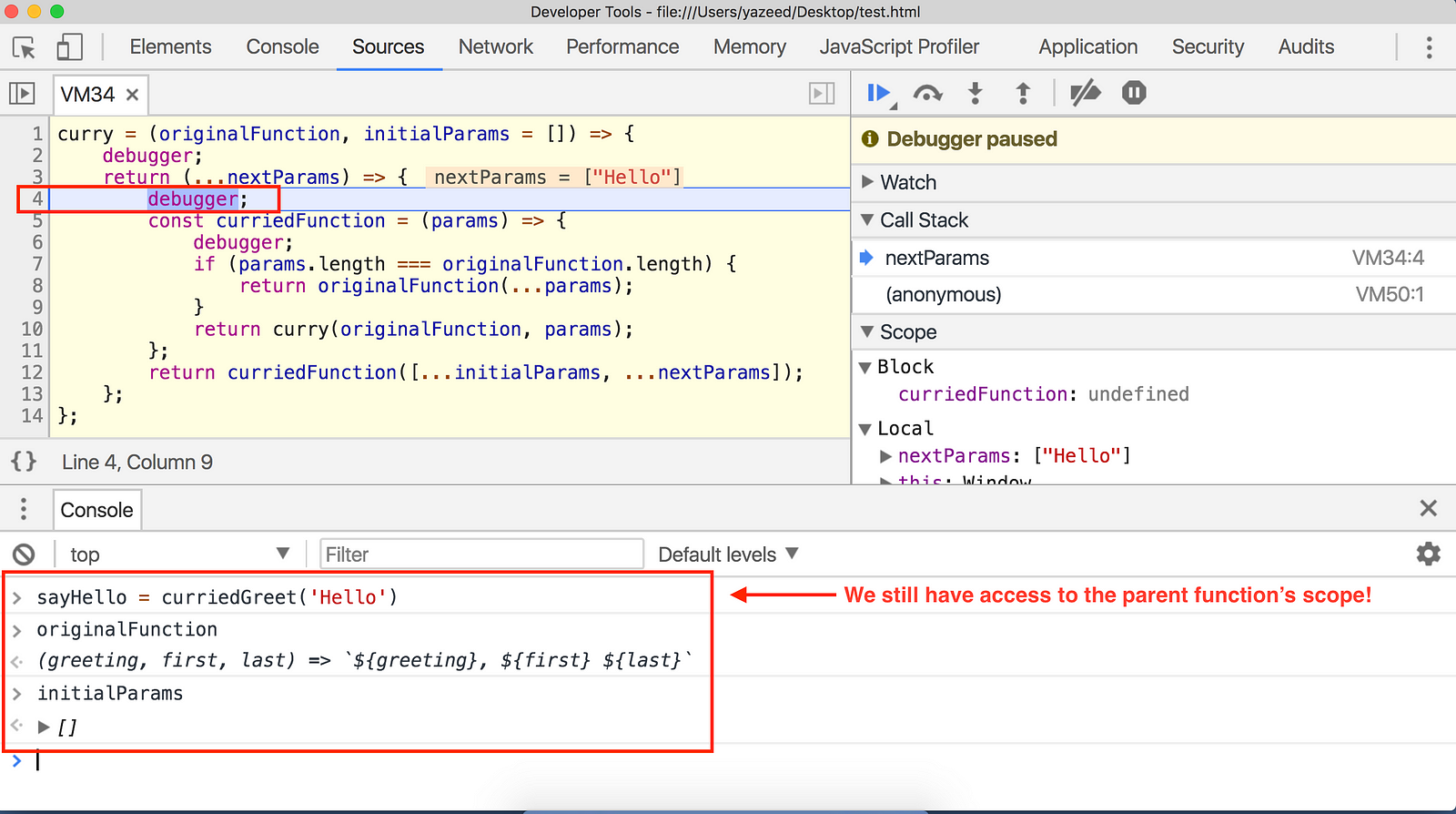

When you’re done playing with that, let’s get a bit crazier and do

sayHello = curriedGreet('Hello').

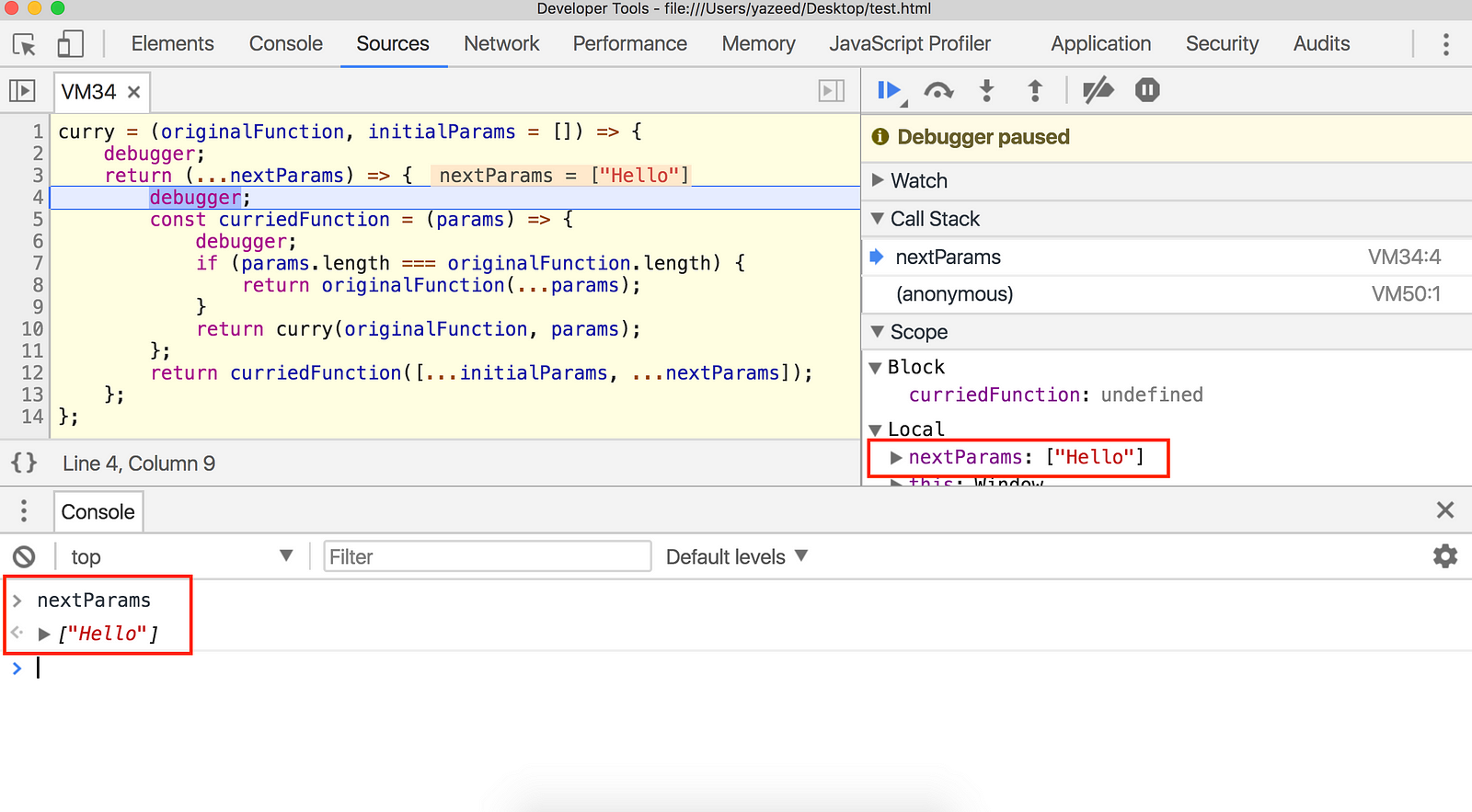

Pause on line 4

Before moving on, type originalFunction and initialParams in your console. Notice we can still access those 2 parameters even though we’re in a completely new function? That’s because functions returned from parent functions enjoy their parent’s scope.

Real-life inheritance

After a parent function passes on, they leave their parameters for their kids to use. Kind of like inheritance in the real life sense.

curry was initially given originalFunction and initialParams and then returned a “child” function. Those 2 variables weren’t disposed of yet because maybe that child needs them. If he doesn’t, then that scope gets cleaned up because when no one references you, that’s when you truly die.

Ok, back to line 4…

Inspect nextParams and see that it’s ['Hello']…an array? But I thought we said curriedGreet(‘Hello’) , not curriedGreet(['Hello'])!

Correct: we invoked curriedGreet with 'Hello', but thanks to the rest syntax, we’ve turned 'Hello' into ['Hello'].

Y THO?!

curry is a general function that can be supplied 1, 10, or 10,000,000 parameters, so it needs a way to reference all of them. Using the rest syntax like that captures every single parameter in one array, making curry’s job much easier.

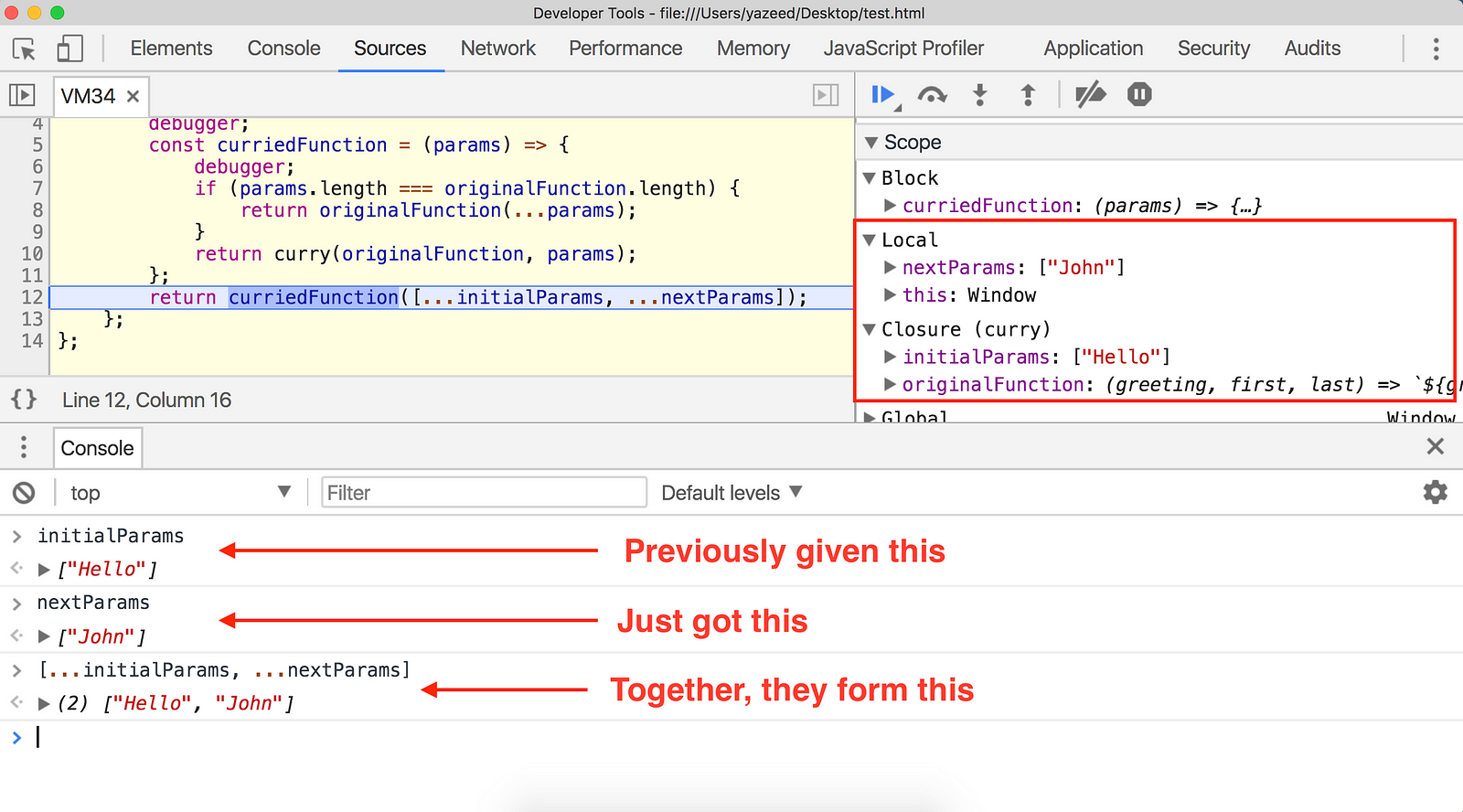

Let’s jump to the next debugger statement.

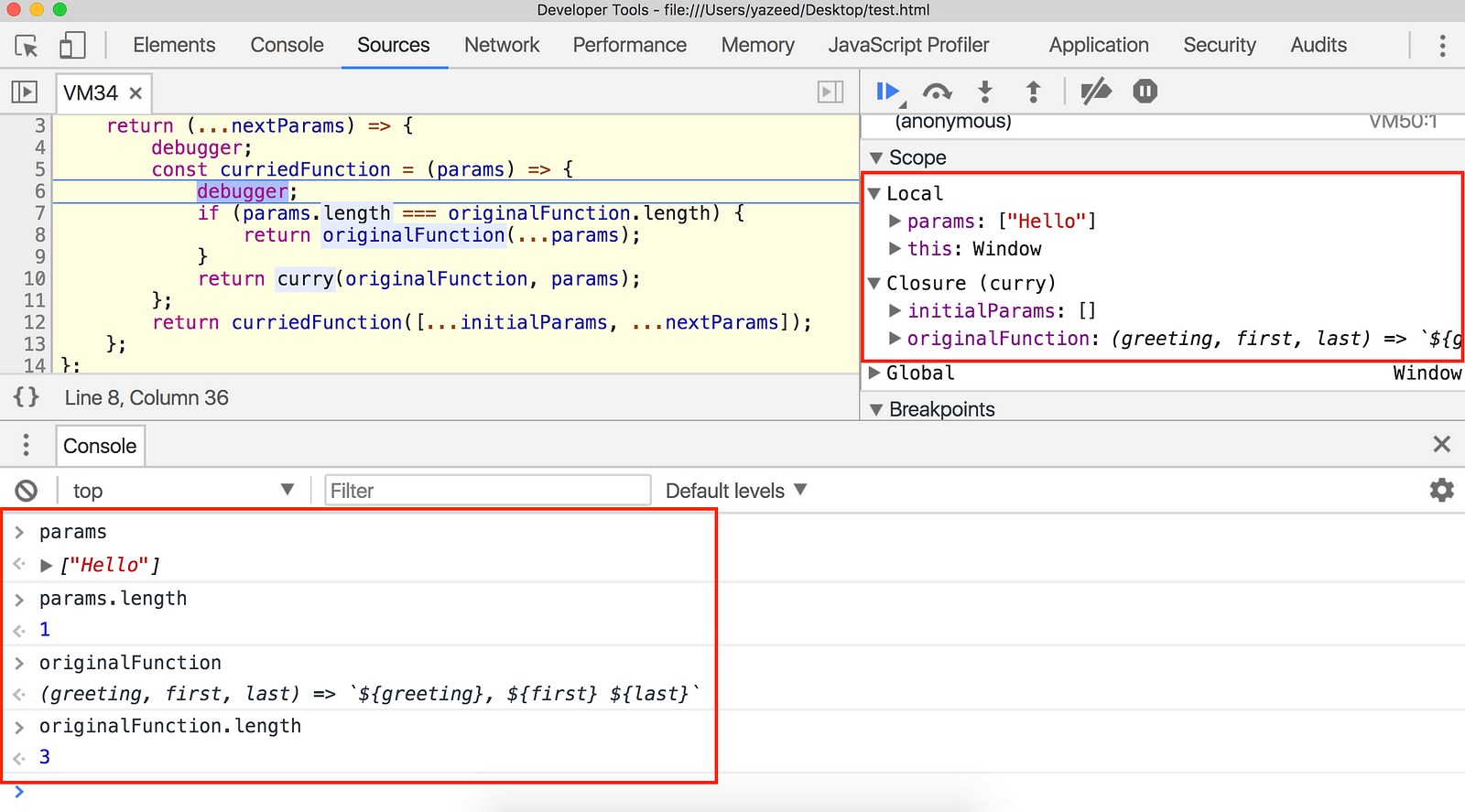

Line 6 now, but hold on.

You may have noticed that line 12 actually ran before the debugger statement on line 6. If not, look closer. Our program defines a function called curriedFunction on line 5, uses it on line 12, and then we hit that debugger statement on line 6. And what’s curriedFunction invoked with?

[...initialParams, ...nextParams];Yuuuup. Look at params on line 5 and you’ll see ['Hello']. Both initialParams and nextParams were arrays, so we flattened and combined them into a single array using the handy spread operator.

Here’s where the good stuff happens.

Line 7 says “If params and originalFunction are the same length, call greet with our params and we’re done.” Which reminds me…

JavaScript functions have lengths too

This is how curry does its magic! This is how it decides whether or not to ask for more parameters.

In JavaScript, a function’s .length property tells you how many arguments it expects.

greet.length; // 3

iTakeOneParam = (a) => {};

iTakeTwoParams = (a, b) => {};

iTakeOneParam.length; // 1

iTakeTwoParams.length; // 2If our provided and expected parameters match, we’re good, just hand them off to the original function and finish the job!

That’s baller 🏀

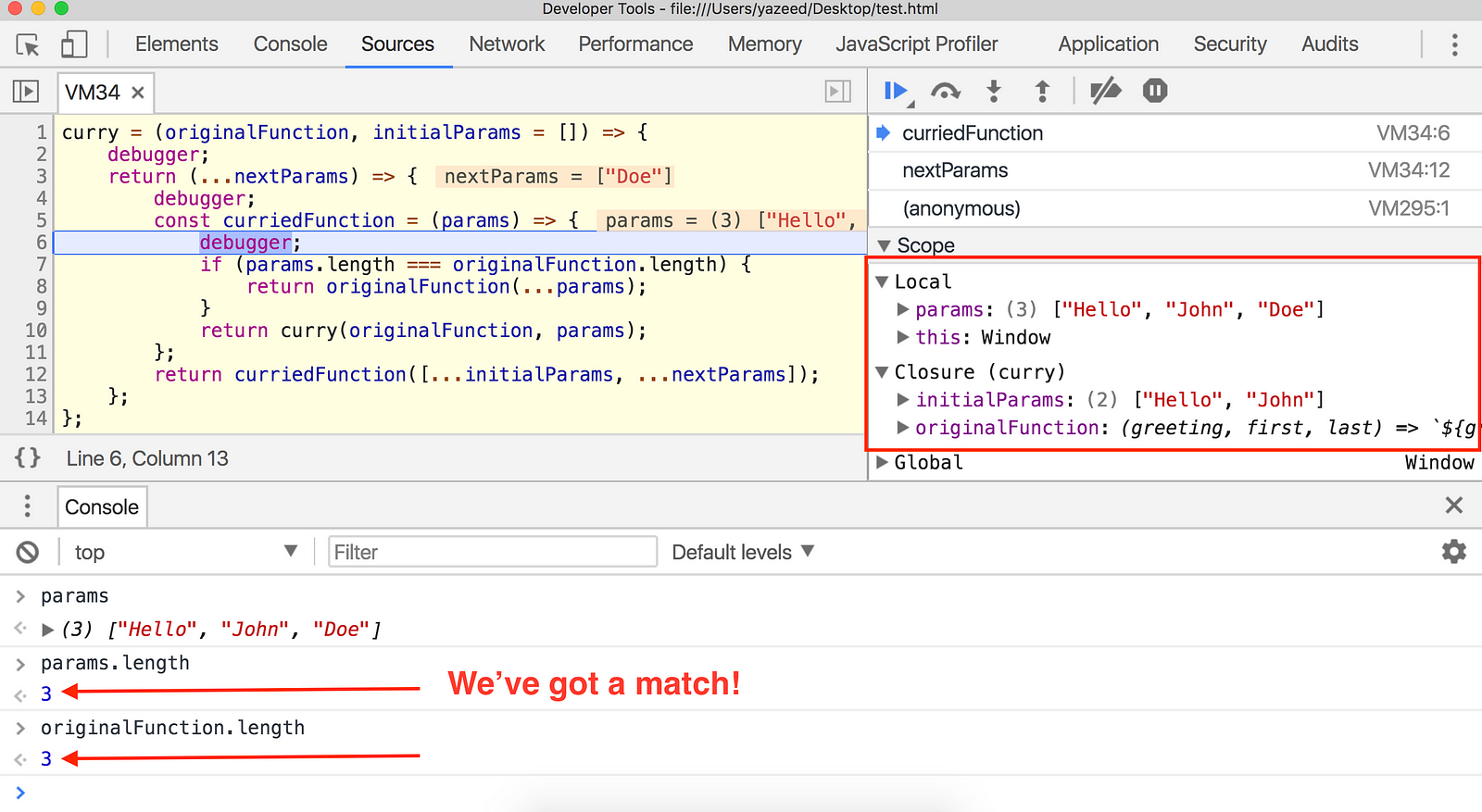

But in our case, the parameters and function length are not the same. We only provided ‘Hello’, so params.length is 1, and originalFunction.length is 3 because greet expects 3 parameters: greeting, first, last.

So what happens next?

Well since that if statement evaluates to false, the code will skip to line 10 and re-invoke our master curry function. It re-receives greet and this time, 'Hello', and begins the madness all over again.

That’s recursion, my friends.

curry is essentially an infinite loop of self-calling, parameter-hungry functions that won’t rest until their guest is full. Hospitality at its finest.

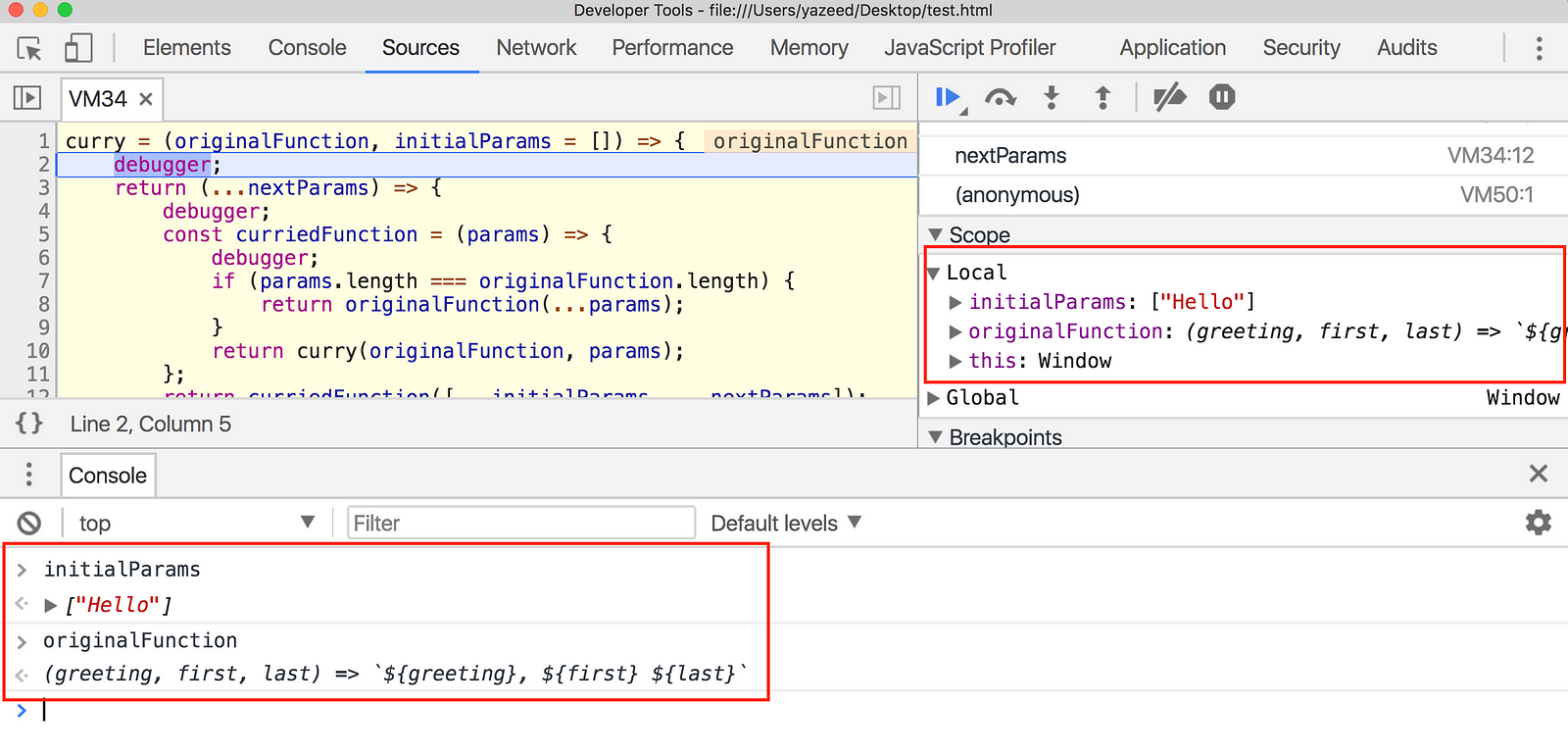

Back at line 2

Same parameters as before, except initialParams is ['Hello'] this time. Skip again to exit the cycle. Type our new variable into the console, sayHello. It’s another function, still expecting more parameters, but we’re getting warmer…

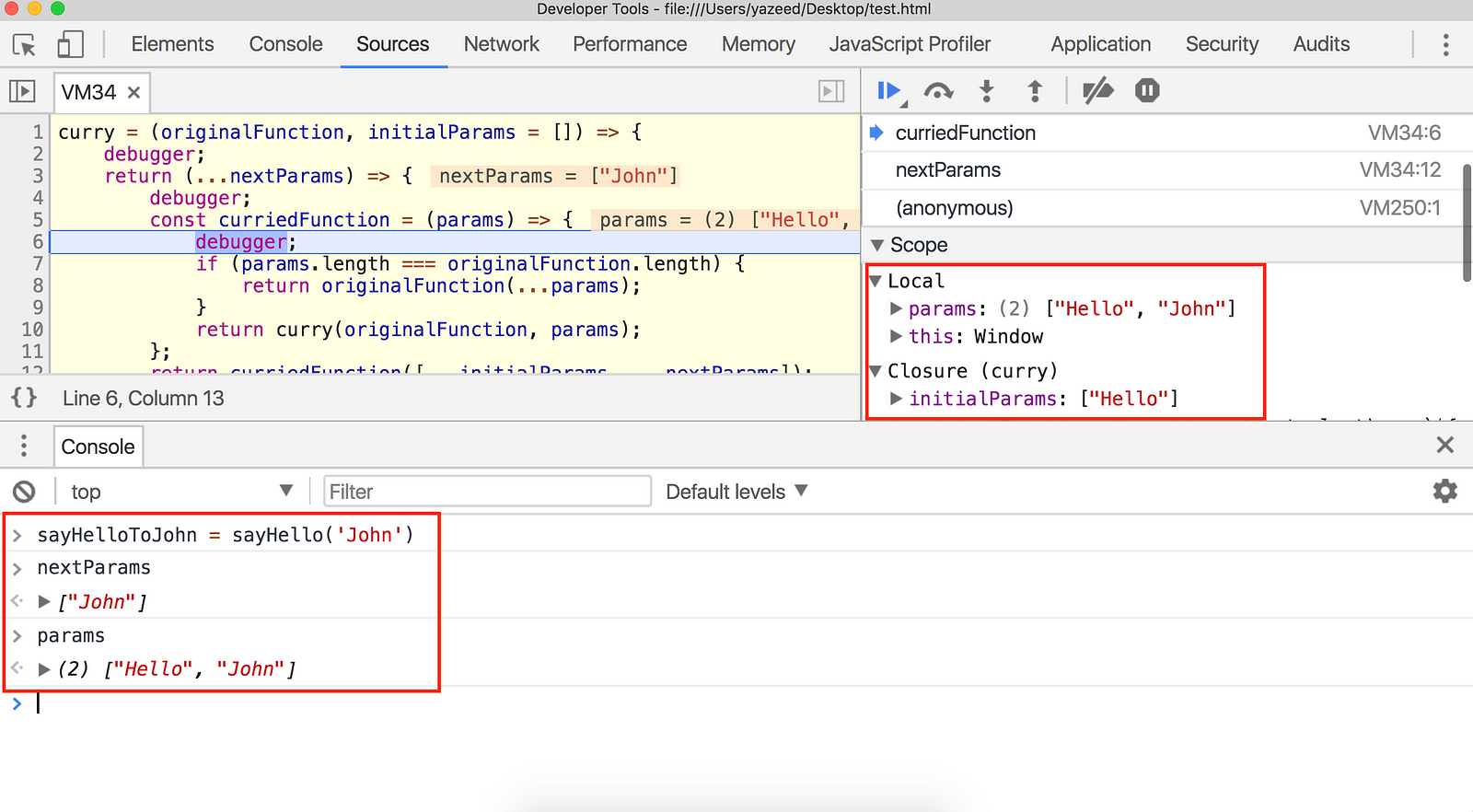

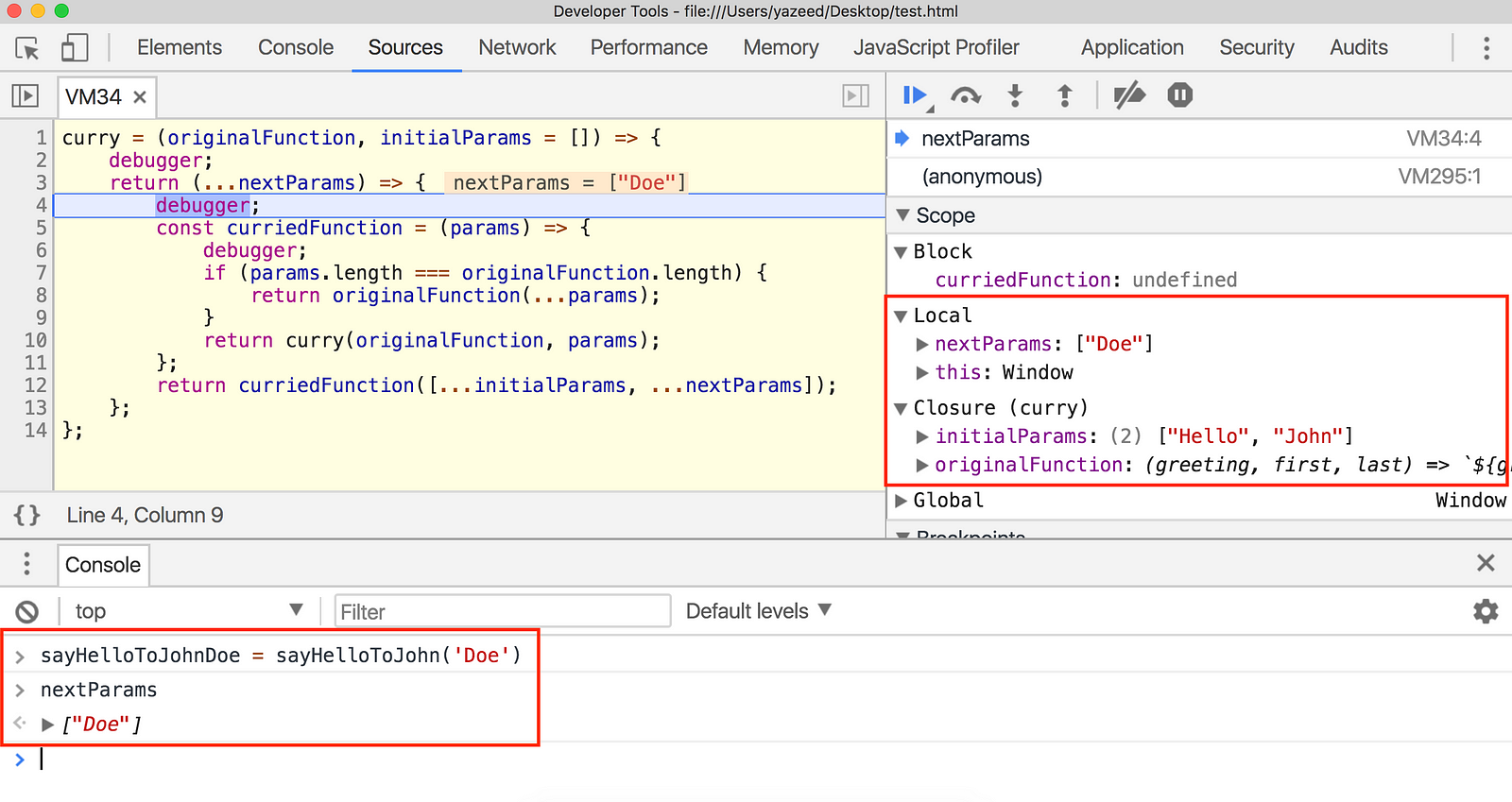

Let’s turn up the heat with sayHelloToJohn = sayHello('John').

We’re inside line 4 again, and nextParams is ['John']. Jump to the next debugger on line 6 and inspect params: it’s ['Hello', 'John']! 🙀

Why, why, why?

Because remember, line 12 says “Hey curriedFunction, he gave me 'Hello' last time and ‘John’ this time. Take them both in this array [...initialParams, ...nextParams].”

Now curriedFunction again compares the length of these params to originalFunction, and since 2 < 3 we move to line 10 and call curry once again! And of course, we pass along greet and our 2 params, ['Hello', 'John']

We’re so close, let’s finish this and get the full greeting back!

sayHelloToJohnDoe = sayHelloToJohn('Doe')

I think we know what happens next.

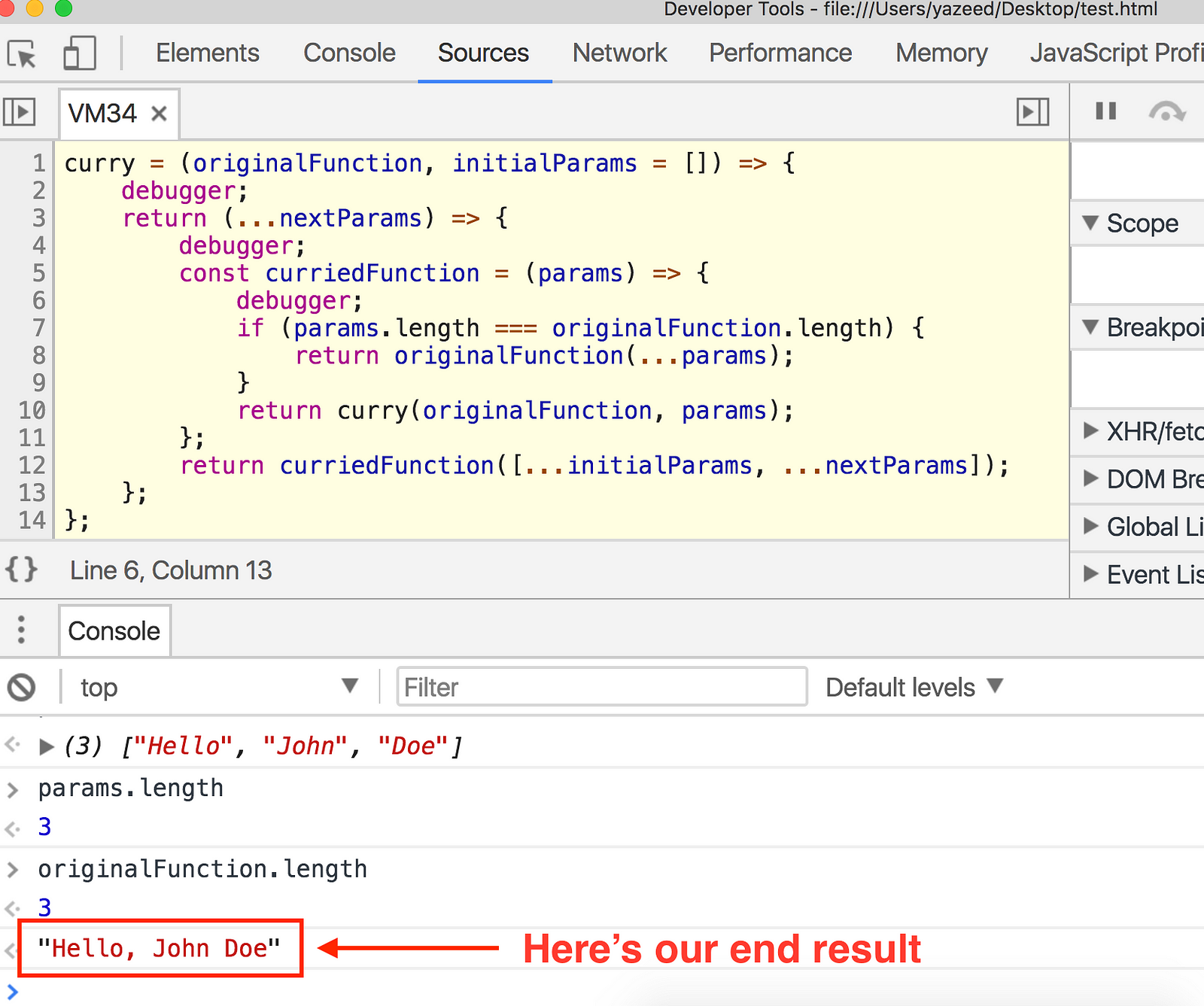

The Deed Is Done

greet got his parameters, curry stopped looping, and we’ve received our greeting: Hello, John Doe.

Play around with this function some more. Try supplying multiple or no parameters in one shot, get as crazy as you want. See how many times curry has to recurse before returning your expected output.

curriedGreet('Hello', 'John', 'Doe');

curriedGreet('Hello', 'John')('Doe');

curriedGreet()()('Hello')()('John')()()()()('Doe');Many thanks to Eric Elliott for introducing this to me, and even more thanks to you for appreciating curry with me. Until next time!